About 22594894

Ciaran MacAirt, Fr. McManus, and John Teggart. Washington, D.C. March 2011. The Irish National Caucus arranged for them to testify at a Congressional Hearing on Northern Ireland.

Nov. 21, 2024

IRISH CONGRESSIONAL BRIEFING

Distributed to Congress by Irish National Caucus

“Ciaran MacAirt has done extraordinary work in exposing British collusion in the McGurk Bar bombing in which his grandmother Kitty Irvine was murdered. How sad he still has to counter England’s Big Lie.”—Fr. Sean McManus

Outrage as Taylor appears to query the “innocence” of McGurk’s massacre victims

Two children were among 15 civilians killed when the UVF detonated a bomb at the bar in 1971

Connla Young. Irish News. Belfast. Thursday, November 21, 2024

FORMER Stormont minister John Taylor is facing criticism after he appeared to question the innocence of 15 Catholics killed in the McGurk’s Bar atrocity.

Mr. Taylor, also known as Lord Kilclooney, made the remarks on social media platform X in recent days.

Fifteen civilians, including two children, were killed when the UVF detonated a bomb in the North Queen Street bar, in north Belfast, in December 1971.

Security forces claims that the IRA was to blame were later shown not to be true.

Mr. Taylor, who was a Stormont minister at the time of the atrocity, wrongly said it was an IRA bomb that exploded prematurely.

During an exchange on X this week the former Ulster Unionist MP again appeared to cast doubt over the innocence of the victims.

The former politician was responding to a post by an account entitled Séamus Bryson’s Attic Trapdoor that referenced the “innocent people murdered in the McGurk’s”, and also urged him to apologize for previous remarks made.

In response the Mr. Taylor said: “You claim they were innocent.”

The following day another post by the same account again referenced the “innocents of the McGurk’s atrocity” to which Mr. Taylor replied, “you clearly do not understand the word ‘innocent’.”

Mr. Taylor’s remarks came after McGurk’s Bar campaigner Sam Irvine, who lost his mother Kitty in the attack, was laid to rest last weekend.

His nephew Ciarán MacAirt was critical of Mr. Taylor’s remarks.

“John Taylor has yet to account properly for the disinformation he parroted in the aftermath of the McGurk’s Bar massacre,” he said.

“This most recent slur occurs just weeks before the 53rd anniversary of the mass murder and cover-up, and just days after the burial of another McGurk’s Bar campaigner.”

Mr. MacAirt said Mr. Taylor’s comments will hurt relatives.

“His baseless slurs will do nothing but hurt the families once again at a particularly difficult time for them,” he said.

In 2018 Mr. Taylor was criticized for claiming McGurk’s Bar was a “drinking hole for IRA sympathizers” who have run a “political campaign to place the blame on the UVF”.

A year earlier he refused to apologize when challenged online by a McGurk’s Bar relative over declaring the atrocity was an IRA ‘own goal’.

Other social media remarks have also caused controversy including his description of former taoiseach Leo Varadkar as “the Indian”, and a claim that unionists and nationalists are not political equals.

MY FIGHT GOES ON

November 20, 2024

IRISH CONGRESSIONAL BRIEFING

Distributed to Congress by Irish National Caucus

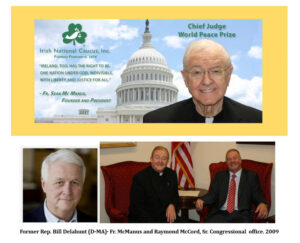

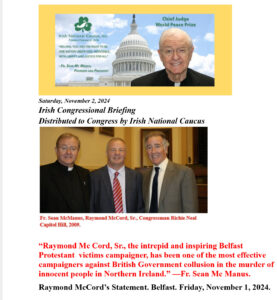

“Belfast Protestant Raymond McCord, Sr. keeps up his unique campaign for justice. Raymond is the first Protestant from Northern Ireland in the current phase of The Troubles to break rank and testify in Congress about British collusion in the murder of a Protestant …That takes extraordinary courage and integrity.”—Fr. Sean McManus.

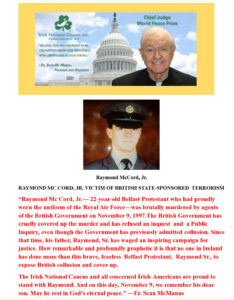

REMEMBERING RAYMOND MC CORD, JR.

RAYMOND MC CORD, JR. VICTIM OF STATE-SPONSORED COLLUSION

Raymond McCord’s Statement

On Thursday, October 31, my solicitors McIvor & Farrell issued legal papers in Belfast’s High Court on my behalf for a Public Inquiry into the murder of my son Raymond, Jr.

Due to the courts shutting down young Raymond’s inquest because of the Legacy Act of the Conservative government—and a senior judge ruling that the Legacy Act is incompatible with human rights, and the most senior judge Lady Chief Justice ruling that ICRIR also set up by the Conservatives is also incompatible with the human rights of victims— I have nowhere else to go except to fight for a full Public Inquiry for my murdered son.

A large part of my legal argument is the fact that collusion between the British state’s Special Branch, a secret department of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, colluded with the proscribed terrorist organization the UVF in the murder of Raymond, Jr. and the cover-up of it.

This is the inquiry the British government and its security agencies fear more than any other because the British government accepted the independent Police Ombudsman report in 2007 that there was collusion between the State Forces and the UVF in my son’s murder. Yet no one has been brought to justice.

I ask politicians and citizens in America to support me in my call for a Public Inquiry, and I take this opportunity to again thank Father Sean McManus, Barbara Flaherty, and the Irish National Caucus in Washington, D.C., for their fantastic support over the years for justice for young Raymond.

On November 9, my son will be dead 27 years, no inquest, no justice, no truth, but I will not give up and on his anniversary, I ask all in America to say a prayer for justice for Raymond, Jr.

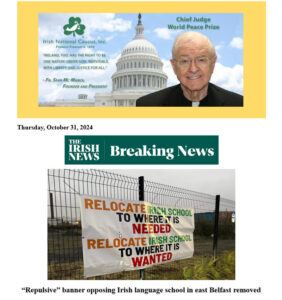

IRISH LANGUAGE

Banner appeared at site of planned Irish medium school at Montgomery Road

By Paul Ainsworth. The Irish News. Thursday, October 31, 2024.

A banner at the site of a planned Irish language primary school in east Belfast calling for it to be relocated to where it is “wanted” has been condemned as “repulsive.”

The banner was placed on a fence at Montgomery Road, where plans have been approved to build a new temporary building for Irish language school, Scoil na Seolta.

The school is set to open later this year but has been opposed by some in the area.

The banner – which has since been removed – stated: “Relocate Irish school to where it is needed; relocate Irish school to where it is wanted.”

Anonymous leaflets were also posted to homes in the area, asking “Do you want an Irish language school in your area?”.

In September it emerged that the Loyalist Communities Council, which represents the views of the UVF and UDA, had advised Stormont DUP education minister Paul Givan that the proposal to build the school should be scrapped during a meeting.

Alliance Party leader and East Belfast MLA Naomi Long condemned the banner’s appearance

“The level of interest in the preschool Naíscoil na Seolta is evidence that it is wanted and welcome and no one has the right to demand they move,” she said.

“It’s hard to imagine how fragile an adult’s sense of identity must be if it is threatened by bilingual toddlers playing in a sand tray or learning to count to ten.”

Alliance Lisnasharragh councilor Michael Long said: “Those behind this are not representative of people in East Belfast, who will rightly find it repulsive and I’d utterly condemn those who put it up.

“Alliance representatives have been in contact with the PSNI and have urged anyone with any information to contact them too. Children have a right to go to school without fear or intimidation.”

SDLP councilor Séamas de Faoite said:“The continued harassment of Scoil na Seolta and those behind the project is absolutely disgraceful. Let’s call this out for what it is – a group of small-minded people, who are in no way representative of the wider community, trying to stop young children from attending school.

“This is not about community concerns, it’s about bitter sectarianism and hatred.”

In a Facebook post, east Belfast loyalist activist Moore Holmes said the banner was a “clear and unambiguous message on behalf of concerned local residents.”

“This site has always been the most bizarre and inappropriate location for an Irish Language School,” he wrote.

“If the local demographic and the political sensitivities around Gaelic language wasn’t enough to sway you, then the mishandling of community engagement, the commercial and industrial nature of the site alongside the disingenuous misrepresentation of community attitudes before Belfast City Council by the organizers would be enough to do it. Relocate.”

*****

A PERSONAL PILGRIMAGE

| By Fr. Sean McManus, President, Irish National Caucus. Capitol Hill, Washington, D.C.

The just-published 420-page book The Barn, by Wright Thompson, is about the barn in which the 14-year-old black boy Emmett Till, visiting from Chicago, was tortured and executed/ lynched in 1955 in Mississippi, and about how so much was covered up, still to this day. Indeed, the barn itself was not generally known as the actual murder site. About 15 years ago, I made a personal pilgrimage to the sacred sites in Mississippi where the civil rights martyrs were murdered: Emmett Till, Medgar Evers, the three activists murdered in Philadelphia (MS), James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, so forth and so on. (And cried silently at each site, just as I do at the graves of Irish patriots who gave their lives for Irish freedom). But I did not know about the barn and only visited the remains of the store in Money in which Emmett had allegedly whistled at the white woman whose husband owned the store. That accusation, true or false, in those days, was enough to guarantee young innocent Emmett’s murder. Thompson says something that is very relevant to the discussion on the Legacy Act of The King-in-Parliament: “The more I looked at the story of the barn… the more I understood that the tragedy of humankind isn’t that sometimes a few depraved individuals do what the rest of us could never do. It’s that the rest of us hide those hateful things from view, never learning the lesson that hate grows stronger and more resistant when it’s pushed underground. There lies the true horror of Emmett Till’s murder… Which is why so many have fought literally and figuratively for so long to keep the reality from view.” (Page 12). ‘Pushing underground…’ That’s the story of the British Empire – the story of The-King (or Queen or Monarch)-in-Parliament… and the story of the Legacy Bill that King Charles III turned into the Legacy Act by his royal assent, which is all about protecting the crown forces and their political bosses (the king being the boss of bosses). Because as George Orwell said: “Who controls the present, controls the past.” For 855 years – and counting – England has controlled Ireland’s present and past. And England is not going to tell the truth about what it did in Ireland or any of the countries it oppressed in its racist, genocidal empire. So, we all have to tell the truth about what England did and is still doing in Ireland. I conclude by referring to another great book (which I made sure to mention in our constant Irish Congressional briefings): Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire (2022) by Harvard Professor Caroline Elkins. How perfect is that title in the context of the Legacy Act of The King-in-Parliament. And, the book blurb on the back page, in part, irresistibly declares: “[Professor Elkins] makes clear when Britain could no longer maintain control over the violence it provoked and enacted, it retreated from the empire, destroying and hiding incriminating evidence of its policy and practices.” And, please God, that is perhaps what the deplorable Legacy Act of The King-in-Parliament also heralds: England’s final withdrawal from Northern Ireland – enabling as the Irish National Caucus internet petition calls for: ‘Ireland, too, has the right to be one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.’ This magnificent petition now has 31,661 signers, with more than 1,000,000 petition views. To sign the petition, go to this link: www.change.org/IrelandOneNation. |

Brexit, backed by the DUP against the wishes of the Northern Ireland electorate, has had a transformational impact on the campaign for Irish unity

Noel Doran. Former Editor. Irish News. Belfast. Monday, October 28, 2024.

IT is always possible to draw different conclusions from separate opinion surveys, allowing for the usual margins of error, so, when questions which do not involve a fixed schedule are involved, it is sensible to examine trends over a prolonged period.

The Good Friday Agreement, for completely valid reasons, took a vague approach in 1998 to the prospect of an Irish unity referendum, and it cannot be disputed that no consequential discussions on the subject followed for many years.

Circumstances have been changing slowly but surely and, while the timing and outcome of a border poll remains uncertain, it is clear that the wider debate is now firmly emerging.

The details of the latest initiative from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), the Northern Ireland General Election Survey 2024, have been closely studied by those on both sides of the argument since they were first published by this newspaper last week, and while at the most basic level the data indicates that the largest group of voters still favor maintaining the status quo, it is the longer-term patterns which are hard to avoid.

It is striking that, even though some observers believe the methodology employed understates nationalist leanings, the latest ESRC findings show that support for the union has fallen below 50 per cent for the first time, sitting at 48.6 per cent, with this figure dropping by more than 10 percentage points over the last decade, and by almost five points in the last five years alone.

Backing for unity is rising at an almost identical rate, up by five points since 2019 to 33.7 per cent, and a particularly telling statistic is that under 25s who expressed a view are evenly split on the union, with exactly 47.7 per cent on each side.

Unionists who believe that nationalists are trying to extract the maximum benefit from the UK’s marginal vote to withdraw from the European Union in 2016, against the wishes of the Northern Ireland electorate, are probably right, and Brexit can be plainly seen as the biggest boost to the campaign for Irish unity in living memory.

It has had nothing less than a transformational impact, as the ESRC statistics confirm, and the evidence is that the unionist advantage which appeared to be impregnable for generations is being relentlessly eroded.

No serious commentator has suggested that unionists might be ready to switch allegiance in a border poll, even before the latest developments in both Belfast and Dublin which have significantly damaged Sinn Féin’s credibility.

However, it will be remembered that Peter Robinson, justifiably regarded as the leading unionist tactician of his era, confidently told a DUP gathering in 2013 that Catholic votes, from those he described as “culturally Irish”, would secure the union in a referendum, which he insisted would be at least half a century away in any event.

The bigger picture has altered substantially since then, after errors of judgment were made in all sections of our society, and a verdict will ultimately be delivered by nationalists, unionists and the unaligned.

Peter Robinson’s latest successor as DUP leader, Gavin Robinson, acknowledged this reality in a speech last week, and it would be fascinating to learn the specific views of both Mr. Robinsons on recent interventions from unionist figures, including some of their party colleagues, over Irish culture.

Continuing onslaughts against GAA members and Irish language enthusiasts, even those of primary school age, have been well documented, and the Assembly questions from Timothy Gaston of the Traditional Unionist Voice which emerged last week represented a new low.

Mr. Gaston, an MLA in North Antrim, demanded to know if a visit by an All-Ireland-winning GAA player to Armagh fire station, in a different constituency more than 50 miles away, was a breach of employment regulations.

The player brought along the Sam Maguire Cup while offering his gratitude to the emergency staff who attended a road traffic tragedy in which three people – two of his close relatives and a friend – were killed last year.

It was a pathetic complaint in every way, which was firmly rejected by the relevant minister, Mike Nesbitt of the Ulster Unionist Party, but it will have an influence on thinking well beyond North Antrim.

Although we need to closely examine health, education, economic, environmental and other issues before a referendum is confirmed, it is beyond doubt that the attitudes exemplified by Mr. Gaston will also be a factor.

n.doran@irishnews.com

Thursday, October 24, 2024.

“GOD REST FR. GUTIERREZ—THE GRANDDADDY OF LIBERATION THEOLOGY—TO WHOM I OWE SO MUCH IN MY OWEN SPECIAL MINISTRY OF JUSTICE AND PEACE.

I highly recommend this excellent tribute from the Jesuit publication, America Magazine.”—Fr. Sean McManus.

R.I.P. Gustavo Gutiérrez, the prophet who revolutionized Catholic theology for the poor

Michael E. Lee. America Magazine. October 23, 2024.

Michael E. Lee is professor of theology and director of the Francis & Ann Curran Center for American Catholic Studies at Fordham University.

Though his landmark book, A Theology of Liberation, came from an era of military dictatorships and guerrilla rebels, the real revolution Gustavo Gutiérrez, O.P., helped usher in was upending how authentic Christian faith could be imagined in the world today. Perhaps more than any other theological figure of the past century, this humble Peruvian priest who died Oct. 22 at the age of 96 wrestled with the question that he identified at the heart of liberation theology: “How do you say to the poor, ‘God loves you’?”

In a world that was coming to understand the structural underpinnings of poverty and violence, and in a church only beginning to confront the challenges of modernity, Father Gutiérrez was a prophet who saw clearly how the Christian proclamation of salvation involved not merely the afterlife but included human liberation in this life as well.

The path to that revolutionary text begins in another era of Catholic theology. Father Gutiérrez, as was typical for many talented Latin American seminarians at the time, went to Europe in 1955 to complete his formation. There he encountered a neo-scholastic theology that emphasized the sharp distinction between natural and supernatural realms.

It was a mindset that worked from abstract principles that could be applied anywhere, anytime—context did not matter. The church was understood as the exclusive vehicle for salvation, a societas perfecta that seemed to have little business with the world except functioning like Noah’s ark to usher souls from the earth’s chaos into the heavenly realm. As a priest, Father Gutiérrez would be expected to minister to his people by turning their eyes from this world’s travails to hope in the eternal rest to come. But he could never accept that separation of the Gospel message from real human experience.

Bedridden between the ages of 12 and 18 with a form of polio, Father Gutiérrez was always sensitive to human suffering and indeed had originally intended to study medicine and psychology. Fortunately, his studies in Belgium, France and Rome (where he was ordained a priest in 1959) also included contact with figures of the “new theology,” like Marie-Dominique Chenu and Yves Congar, whose historical studies of ancient and medieval Christian theology forged a path away from abstract Neo-Scholasticism.

The lesson that Father Gutiérrez would take from these encounters was twofold: First, all theology is contextual and dynamic, and second, behind every theology lies a spirituality. These insights contributed to the dramatic changes associated with the Second Vatican Council.

Yet, for all of its accomplishments, particularly in addressing the “nonbeliever” in the modern world, Vatican II did not sufficiently account for the ones that Father Gutiérrez called the “non-persons.” If the church were going to participate meaningfully in the world, it needed to respond to the reality lived by the majority of earth’s inhabitants—one of poverty and exclusion.

Though he often worked with college students, Father Gutiérrez did not hold a university position until much later in his life. His theology emerged not from the halls of academia but as a response to the questions and concerns he heard from parishioners in the poor Rimac neighborhood of Lima.

Of course, while his theology may have been nourished at this local level, it would quickly make a global impact. In 1968, Father Gutiérrez served on the theological commissions for the seminal Latin American bishops’ conference meeting in Medellín, Colombia. Its documents served as a clarion call for the re-conceiving of the Catholic Church’s role in Latin America and, indeed, the world.

The 1971 publication of A Theology of Liberation (the English translation appeared in 1973) ushered in the dynamic—and controversial—eponymous theological movement and established Father Gutiérrez as its most important voice. Its insights are too numerous to catalog, but it is safe to say that it remains one of the most significant works of 20th-century thought. In it, Father Gutiérrez lays out ideas that he would pursue and refine for the rest of his career.

He describes theology as a “critical reflection on Christian praxis in light of God’s word.” It is a second moment that follows a first moment of mystical encounter with God in and through action in the world. That second moment is crucial because the encounter with poverty and oppression demands not just a one-way Christian response. It calls for a rethinking of Christian ideas themselves in light of those horrible realities, and this dynamic explains the very meaning of the term “liberation theology.”

Father Gutiérrez concluded that in the encounter with violence and poverty, a notion of salvation as an exclusively otherworldly hope was inadequate. Surely the God of the Exodus, the God of the prophets, the God whose reign Jesus preached and the God who took flesh in the world offered more. Father Gutiérrez plumbed the depths of salvation as human beings’ communion with God and with each other. Though its fullness is a future hope, it must begin in the present.

Liberation and salvation, then, are synonymous for the gracious activity of God. Liberation theology is really a theology of salvation, with profound implications for how Christians live, believe, pray and act today. To reflect on Jesus as a liberator, to consider sin in its social and structural dimensions, to ponder the implications of the church’s mission to proclaim truly good news to the poor—these are the fruits of a liberation theology.

Certainly, the new insights generated by liberation theology unsettled traditionalist understandings of the faith and the church. After all, in Latin America, the Catholic Church, with few exceptions, had been a keeper of the status quo since colonial times. It was jarring to many to envision it cutting its alliances with the powerful and proclaiming a salvation that meant integral human development for all peoples. Under liberation theology, peace is not simply the absence of violence but is also the positive presence of justice; it is a personal and structural reality that calls for continual conversion by the church and all of its members.

The signal achievement in Father Gutiérrez’s thinking is his theological treatment of poverty. As a young priest, he wondered how Christianity could speak of it in often beautiful terms, even in the face of poverty’s dehumanizing effects. Clearly, different meanings of the term poverty needed to be distinguished without ignoring its basic, material meaning. But whether it be the lack of material resources to survive or the deprivation of basic human rights, Father Gutiérrez said, poverty in its basic, material meaning is unequivocally evil and must be regarded theologically as sin. This kind of poverty, he would often say, means death, death before one’s time. Any other understanding of poverty comes after this basic one and must address it.

But looking at the Bible and Christian tradition, Father Gutiérrez also identified two “positive” senses to the term poverty. The first is a sense of poverty as humanity’s utter dependence on God. This “spiritual poverty” is one that all people should cultivate, though not by ignoring the reality of material poverty. Rather, Father Gutiérrez linked spiritual poverty to a third sense of poverty as commitment, as solidarity with those who suffer the effects of material poverty.

This solidarity takes on a range of forms, from the merciful care of those who are poor to the prophetic denunciation of the causes of material poverty. Most importantly, the interaction of these three senses of poverty calls for a spirituality, a contemplative-active commitment on the part of the church to make the world more closely resemble the reign of God that Jesus preached.

This spirituality is captured in the often misunderstood phrase “the preferential option for the poor.” By it, Father Gutiérrez gave voice to a disposition, a priority, a way of life that follows the paradoxical Gospel injunction that the “last shall be first.” Christian disciples are called to confront the reality of poverty in all of its complexity. They must prioritize the poor and opt (noting that it is not optional) on behalf of those who are poor.

This principle, which has been adopted and elaborated in modern magisterial texts, has come to be a defining feature of Catholic social teaching. It is more than an ethical injunction, however. In Father Gutiérrez’s work, the preferential option for the poor is a mystical experience; it is God’s own self-revelation. God’s love, expressed time and again in Scripture, is not exclusive but prioritizes those who are weakest. In the words of the 16th-century Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas, about whom Father Gutiérrez produced a massive tome, “God has a very fresh and living memory of the smallest and most forgotten.”

For decades, Father Gutiérrez’s theology drew suspicion in Vatican circles and from those privileged sectors of the Latin American church that felt threatened by its challenges. In the face of queries, suspicions and threats, Father Gutiérrez remained serene and responded to critics thoughtfully. His book The Truth Shall Make You Free offers an account of theology’s relationship to the social sciences and a forceful response to those who would caricature him as a Marxist.

In the end, he was vindicated. Father Gutiérrez was never censured, nor his work ever judged to be heterodox. To his critics’ dismay, he co-published books with the former prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Cardinal Gerhard Müller. By the turn of the new millennium, he had entered the Order of Preachers (Dominicans), taught at their prestigious school in Rome (the Angelicum) and was even given the title magister sacrae theologiae, an honorific bestowed upon the great medieval figures St. Albert the Great and St. Thomas Aquinas.

I recall attending the seminar of a sociologist who claimed to have worked with Father Gutiérrez for a short time in Peru. The speaker lamented that Father Gutiérrez had sadly “left behind the early liberation stuff” when he began writing on spirituality. Nothing could be further from the truth.

From works like We Drink From Our Own Wells or his personal favorite, On Job, Father Gutiérrez demonstrated how profound faith and social commitment are organically intertwined. It is a thoroughly incarnational theology that testifies to God’s presence among human beings and the call of all believers to participate in making the world more closely resemble God’s will for human flourishing.

In that sense, when the poor take center stage, they are not merely receivers of the good news (though they are). Rather, their struggles illuminate the reality of the world and reveal the mysterious presence of God that human language and understanding can only reach toward. This is why Father Gutiérrez repeatedly emphasized that the preferential option for the poor is a theocentric option that believers in the church, much like Job, need to witness; they need to hear God’s own option in revelation and adopt that example in their very lives.

Yes, even the poor need to make the option for the poor.

Most readers overlook the double dedication of A Theology of Liberation. Father Gutiérrez devoted the book to the mestizo Peruvian novelist José María Arguedas, who vividly portrayed the circumstances of Indigenous Andean peoples, and to the Black Brazilian priest Henrique Pereira Neto, who was kidnapped and tortured under military dictatorship. This pair was chosen to symbolize the two great marginalized populations of the continent, Indigenous and African.

Hearing those voices on the margins and putting their concerns at the center of theological thought—that is the lasting legacy of Gustavo Gutiérrez. He did not attempt to make Christianity “relevant,” but he showed that when Christian faith responds authentically to human suffering, it fulfills its deepest calling. Gustavo Gutiérrez was both a prophet who denounced the abuse of the marginalized and a mystic who saw God’s presence where it seems most absent.

From 2023: 50 years later, Gustavo Gutiérrez’s ‘A Theology of Liberation’ remains prophetic.

From 2003: An interview with Gustavo Gutiérrez.